Article 7

Discrimination and the Suburban Boom

Courtesy of the National Archives

Discrimination and the Suburban Boom

ViewHide Transcript

How did America become a nation of suburbs?

The federal government was the major force making this possible and it accelerated after World War II.

Before the war, most Americans were renters.

The modern foundations for suburban growth were established in 1944 with the passage of the GI Bill. It gave returning servicemen a range of benefits, including education funding, job training, and low-cost home loans.

Millions of White veterans took advantage of this new pathway to homeownership.

But it was a different story for veterans of color. Even though the law did not explicitly exclude them, racial discrimination by the banks prevented most from accessing their benefits.

The federal government also fueled the suburban boom through investment in highways.

The earliest suburbs developed as a way for Americans to escape crowded cities while still being close enough to commute to work via streetcar or railroad.

In 1956, the Federal Highway Act was passed, and America’s interstate highway system was born. The act authorized 41,000 miles of new interstate highways. But for new roads to be laid down, there was a sacrifice. Black and Latino families bore the brunt of it. They saw their neighborhoods demolished or bisected while White neighborhoods were most often spared.

The new highways made it faster and more affordable for suburbanites to commute to cities. But it was mostly White homeowners who enjoyed these benefits.

The exodus of White families moving to the suburbs became known as “White flight.” Approximately two White people left northern cities for every Black person who arrived during the Great Migration.

Even families of color who could afford the suburbs were excluded through discriminatory practices, such as steering and racially restrictive covenants.

Meanwhile, White suburbanites justified their segregated communities by focusing on their rights as homeowners and taxpayers. They felt they had the right to control who their neighbors were without the government interfering.

Together, these forces helped White families realize the American dream of homeownership. But families of color were largely left out. Some formed their own suburban communities while many stayed in the cities.

The effect of these disparities would be felt for generations, widening the wealth gap between Black and White Americans as properties in White suburbs rose in value.

How do you define the American Dream?

Has your family achieved the American Dream?

Why is it associated so heavily with the suburbs?

From 1920 to World War II (WWII), most Americans were renters living in cities. As cities grew, people settled along streetcar and rail lines, building diverse neighborhoods of mixed races, classes, and ethnicities. But after WWII, the federal government radically reshaped living patterns, creating the new, and mostly White, middle-class suburb.

In places like Naperville, Illinois, farmland was converted into suburban tract housing during the postwar boom. Aerial view of Moser Development.

Courtesy of the Naperville Heritage Society

In 1944, the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act (known as the GI BillServicemen’s Readjustment Act, 1944: The Servicemen’s Readjustment Act, more commonly known as the GI Bill, was a Congressional Act created to aid the reentry of American veterans returning from World War II. Benefits included assistance for education, vocational training, housing, business loans, unemployment insurance, and later healthcare. Minority veterans experienced discrimination when attempting to access GI Bill benefits.) provided benefits for WWII veterans. Returning soldiers were offered low-interest home loans with no down payment, small business loans, college or trade-school tuition, and unemployment benefits. These programs changed lives, making home ownership and higher education an achievable dream for millions of White veterans.

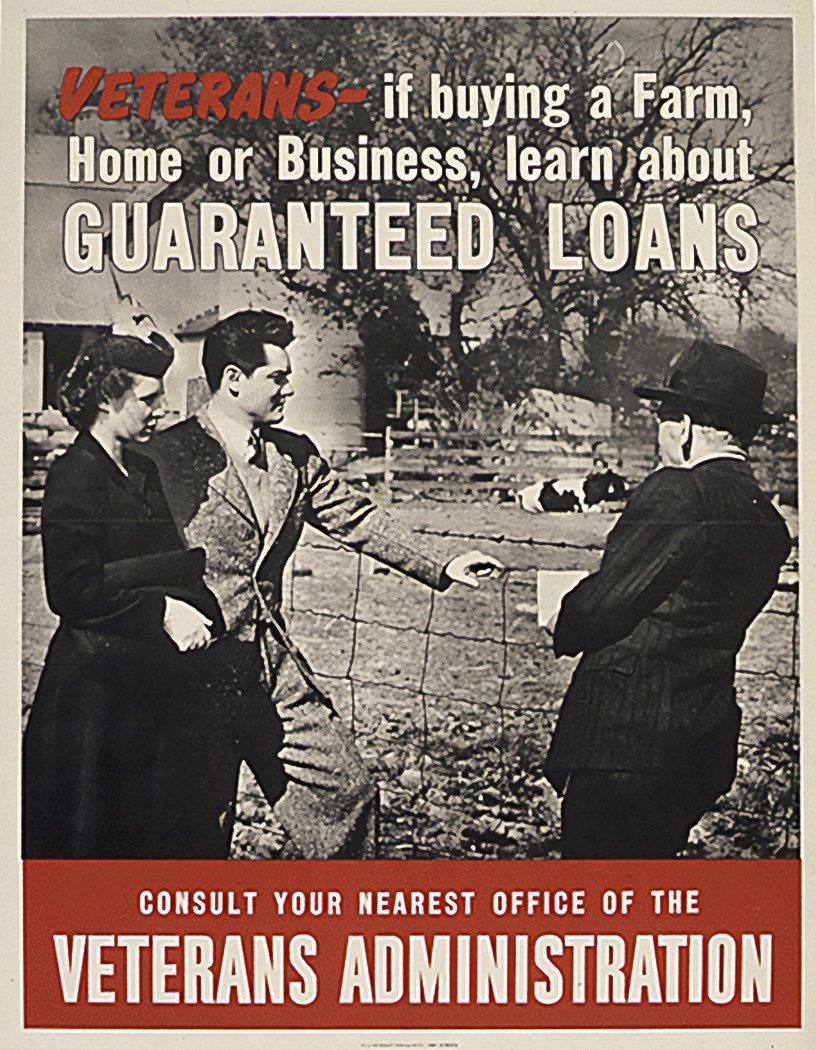

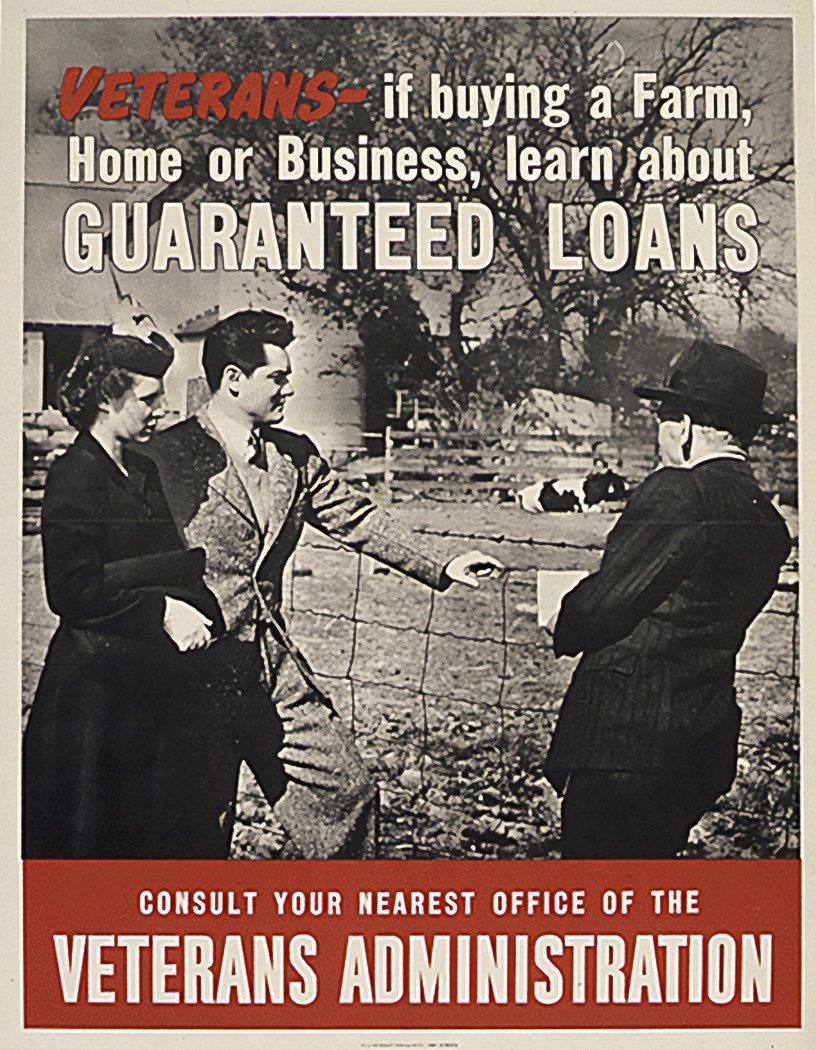

A World War II-era poster alerting veterans buying property or starting a business to contact the Veterans Administration to learn about guaranteed loans.

Courtesy of the National Archives

But for Black and other veterans of color, accessing GI benefits was not so easy. Benefits had to be arranged through local banks, schools, and real estate agencies, many of which still refused to serve people of color. Those who tried to apply for the programs were often intimated, harassed, or singled out for violence.

This early-1940s ad for General Electric details the promise of prosperity that would follow victory in World War II. Not only would new homes in the suburbs be available, but they would be filled with the most modern conveniences.

Courtesy of the Life Magazine

Without such barriers, White people could use these programs as a stepladder to the American Dream. Government-funded education often brought higher earning power. That meant easier access to home loans and the chance to move to a newer, bigger house. White buyers took advantage of new home loan programs, growing their rate of home ownership from 44% to 62% between 1940 and 1960. Many purchased newly built homes in new suburban developments. Meanwhile, Black homeownership, already lower, grew much more slowly: from 23% to 38%.

White homeownership in the suburbs gave rise to the concepts of “homeowners’” and “taxpayers’ rights.” Many Whites asserted that because they owned property and paid property taxes, they had the right to select their neighbors and their children’s classmates or sell to buyers of their choosing without government interference. A Naperville, IL homeowner wrote to the local paper in 1968: "I am not anti-Negro but I am vehemently against losing my private property rights. By passing a forced housing ordinance, the Negro does not gain any rights, but in fact, loses the same private property rights that I lose."

White homeowners argued that their success (and the failure of inner-city neighborhoods), was due to individual determination or impartial market forces instead of racist policies and exclusionary practices. Efforts to end racial disparities in their neighborhoods were seen as attacks on their rights. In the suburbs, entire local governments had no Black and immigrant constituents. Municipal tax dollars were used for schools, playgrounds, and libraries that benefited only local White homeowners.

For the children of European immigrants, neighborhood segregation decreased as they joined American-born White families in the suburbs and assimilated into a White American identity. Black Americans experienced the direct opposite. For them, discriminatory practices increased segregation rates from 1890 through the twentieth century.

So that is what I think was the community experience of people who were constantly having to make an adjustment that none of us talked about.

Attorney and Wealth Manager

ViewHide Transcript

One of the things I think people are just not getting is, they'll say, “You know... Why don't you guys just drop this stuff and all of this race and being Black? I mean, it's nothing.” Well, growing up in Wheaton, DuPage area, you had to be aware of your race, of your color, of your ethnicity, 24/7. So when you would go in school... It's like, I've got a good picture of it now that I thought about. It's like, think about somebody putting their hand on your shoulder all the time. And after a while, you don't notice it until, and the way I figured it out is I would go to church, and all of a sudden I feel lighter. I used to think that was Jesus, but it probably was, that's the truth it was. It really was the fact that I was in a safe space.

I was in a safe space. And so the pressure was gone. I could be myself. And the interesting thing about churches, we actually acted like African-Americans. We fully went into our culture. Which is why White folks tended not to stay if they came because it wasn't like the church was going to mean any White person go to a Black church. We all thought, let's never throw White people out. Think about that, that don't make any sense. But they won't stay because they go, “Oh my gosh, this culture is so different. We feel...” Ah, that's right. You feel like we feel all the time. And so that's the point. And so that is what I think was the community experience of people who were constantly having to make an adjustment that none of us talked about.

The growth of the suburbs in the mid-twentieth century only increased the Black/White wealth gap. To this day, the United States remains the only majority suburban nation in the world.